CAD026: Convex Lisp

Overview

Convex Lisp is a general purpose, high level programming language for the Convex Virtual Machine (CVM), designed to facilitate effective construction of smart contracts, digital assets and open economic systems.

This document outlines the key elements of Convex Lisp. It is intended primarily as an introduction and programmer's guide for experienced developers wishing to understand the language, its implementation and key features: more detailed specifications for specific aspects of the language and underlying runtime are provided in other CADs.

Key language features

- Pure immutable data structures with highly optimised implementations for usage in decentralised systems based on Convex

- Emphasis on functional programming with support for the lambda calculus

- Powerful macro capabilities, following the expansion-passing style developed by Dybvig, Friedman & Haynes

- Automatic memory management, including memory accounting

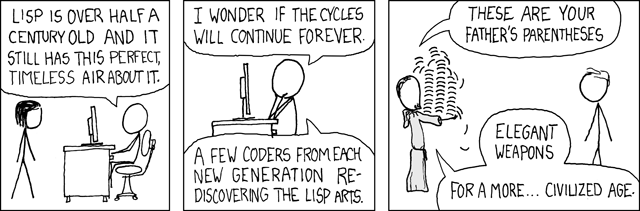

- Elegant Lisp syntax largely inspired by Clojure

- On-chain compiler (smart contracts writing smart contracts....)

- Strong dynamic typing - for well defined, consistent behaviour at runtime

(Image courtesy of XKCD)

Motivation

As a platform for decentralised, open economic systems Convex requires a powerful and flexible language for developers to build the next generation of digital assets, smart contracts and services.

While the CVM itself is language agnostic, we chose a Lisp dialect as the first language for Convex for a number of key reasons:

- Productivity: general recognition of Lisp as a productive and flexible language

- The advantages of a homoiconic language ("code is data") for generating code with powerful macros and DSL capabilities

- The ability to create a small and efficient compiler suitable for on-chain code generation and compilation

- Familiarity for developers of existing Lisp-based languages such as Clojure, Scheme, Racket or Common Lisp

Designing a new language is no easy task, so we naturally considered adopting an existing language for Convex. Unfortunately, none of the available options proved attractive for a variety of reasons:

- High level general purpose programming languages (Python, Java, JavaScript, Clojure, C# etc.) are not generally designed for decentralised VM operation. In particular, execution must be deterministic to allow independent execution and validation of the same exact computation by peers in a decentralised network. Cutting down such languages to a consistent deterministic subset (no IO, no randomness, no observable differences across platforms etc.) would itself be a massive task and break compatibility with the majority of existing code, negating most of the value of existing library ecosystems.

- Low level languages (WASM etc.) do not provide the high level capabilities and abstractions needed for productive development of decentralised economic systems. The amount of library support required to provide this would be a significant development and performance overhead. Typically, such languages also lack good support for automatic memory management which is important for developer productivity and essential for the kinds of immutable data structures used in Convex. These languages would also imply complex toolchains and execution infrastructure that would add complexity and inhibit development and maintenance efficiency.

- Existing smart contract languages (Solidity etc.) have significant limitations / design flaws and would not allow us to take full advantage of the power of the CVM (e.g. the improved account model with key rotation, memory accounting, extra CVM data structures etc.).

- Convex performance at global scale depends heavily on very efficient immutable data structures that are not easy to represent in existing languages that were not designed with these in mind. No existing language would be a good fit for these natively, and translating to / from these structures would imply an unacceptable performance penalty: we need to use them directly.

Discussion and contributions

Questions or discussions on Convex Lisp including design choices and potential improvements are encouraged on the Convex Discord in the #language-design channel.

Interactive development

Convex Lisp is designed to support interactive usage. By compressing the traditional write / compile / test / debug cycle, developers can write code more efficiently and work directly with (including modifying) a running program.

Typically, developers will make use of a REPL (Read-Eval-Print-Loop) which executes expressions directly to return a result (and possibly also modifying the CVM state). REPLs can be used in local test environments, or directly on a deployed Convex network.

It is possible (though not usually recommended, for obvious security and risk reasons) to enable REPL capabilities on live production code. This capability can be used to hot-fix and upgrade running CVM code.

Examples given in this CAD are suitable for execution at a Convex Lisp REPL.

Expressions and Forms

Convex Lisp code operates through the evaluation of expressions. Expressions are represented as CVM data structured as a "form" - a data value that represents code. In this sense "code is data" because the language is represented in its own data structures. This property is sometimes termed homoiconicity.

Typically, a form is a List where the first element represents the operation and the following elements represent arguments, e.g.:

(operation arg1 arg2 .... argN)

Each element is itself a form - so forms can be nested to construct more complex expressions.

At the lowest level, forms will be a single (non-compound) data value that does not contain any further elements. These are sometimes called "atoms" in Lisp literature:

;; the following are all atomic forms

1

hello

"This is a string"

Data types

Convex Lisp provides a rich set of data types suitable for general purpose development. These include:

- A superset of JSON for easy interoperability with web based systems

- Immutable persistent data structures with automatic structural sharing

- Binary Blobs for arbitrary user-defined data and interoperability with external systems

- Indexes for database implementations with efficient sorted keys

Convex Lisp directly uses the data types provided natively by the CVM, for maximum efficiency.

For more detailed specification of CVM data types see CAD002

Basic Literal values

Literal values are expressions that evaluate to themselves (as a constant). These include numbers, strings, booleans etc.

Integers

Integers are positive or negative integer values. Most typical mathematical operations are supported.

1

=> 1

(+ 2 3)

=> 5

The CVM supports "Big Integer" mathematics natively, with values up to 2^32768 (4096 bytes). Typically, most integers require less than 64 bits, so are stored efficiently as 64-bit long integers in the CVM implementation, switching to a Big Integer representation only when required. To the user, there is no visible difference apart from paying somewhat higher transactions fees to fairly reflect the additional computation requirement.

;; A large negative big integer

-9999999999999999999999999999999999999999

=> -9999999999999999999999999999999999999999

;; Big integer mathematics (this would overflow 64 bits)

(* 100000000000000000000001 987654321)

=> 98765432100000000000000987654321

Key motivations for including big integer support in Convex Lisp include:

- Avoiding the risk of numerical overflow when performing computations on large numbers such as asset balances

- Supporting 256-bit integers commonly found in other decentralised systems

- Supporting cryptographic applications which rely on large integers (e.g. 4096 bits)

Doubles

Doubles are 64-bit double precision floating point vales, as specified in IEEE754

;; Double values are literals, just like Integers

12.45

=> 12.45

See below for more details on floating point support in Convex Lisp

Booleans

Booleans are either true or false

true

=> true

false

=> false

Booleans are primarily used in conditional expressions, or as return values from predicates.

Characters

Characters are Unicode code points (equivalent to 1-4 bytes in UTF-8 representation)

;; character literals can be specified with a leading \

\a

=> \a

;; characters can also be specified by numerical Unicode code points

(char 65)

=> \A

Characters are mostly useful for constructing Strings.

Characters may also be used as efficient small keys in Maps or Sets. The first 256 code points (equivalent to ISO-8859-1 characters) encode to just 2 bytes and are efficiently cached, though care should be taken that some of these values are not always correctly printable.

Strings

Strings are arbitrary length, immutable UTF-8 strings

;; A a literal String evaluates to itself

"Hello"

=> "Hello"

;; Constructing a String

(str "A" "BCD" "EF")

=> "ABCDEF"

Strings are provided to enable human readable output, for programmer convenience and for compatibility with JSON. Typically, string processing should be avoided on the CVM - while possible this is usually best done on the client side or on a separate server backend.

Blobs

Blobs are arbitrary length sequences of byte data. These are particularly useful in Convex for:

- Representing cryptographic values such as hashes and Ed25519 public keys

- Allowing applications to store custom data in their own encodings

Blobs can be easily constructed as literals by prefixing 0x to a hexadecimal representation of the byte data

;; A small Blob literal

0x1234ee99

=> 0x1234ee99

;; Can use functions like `count` to get the length of a Blob

(count 0x12e5)

=> 2

Addresses

Addresses are identifiers for accounts on Convex (either user or actor accounts). They are expressed as positive integers preceded by #

;; An address literal

#123678

Data Structures

Data structures are composite values containing other values as elements.

In Convex Lisp, all data structures are immutable, in the sense that once an instance is constructed, it cannot be modified: however a new instance can be constructed with any desired modifications extremely efficiently (most importantly this does not require copying the entire data structure - the unchanged elements are shared with the original instance)

Vectors

Vectors are the most common data structure, representing an indexed sequence of elements. They can be constructed by square brackets [ ... ] or with the core function vector

[1 2 3]

=> [1 2 3]

(vector true 0x1234 "Hello")

=> [true 0x1234 "Hello"]

;; concatenate two vectors

(concat [1 2 3] [4 5 6])

=> [1 2 3 4 5 6]

;; append a new element

(conj [1 2 3] 4)

=> [1 2 3 4]

You should use Vectors in most cases when you would use an "array" or "list" as defined in other languages.

Vectors are particularly efficient for operations that add/remove at the end of the Vector.

Lists

Lists are sequential data structures most commonly used for expressing Convex Lisp code. They are represented by surrounding zero or more elements with regular parentheses ( ). Because they are interpreted as code, if you want to construct a List literal you must quote it to suppress evaluations with '( ) or use the constructor function list

;; Note single quote symbol needed to produce a literal List

'(1 2 3)

=> (1 2 3)

;; This also works

(quote (1 2 3))

=> (1 2 3)

;; This fails, because it gets interpreted as a function application, and "1" isn't a function!

(1 2 3)

=> Exception: :CAST Can't convert value of type Integer to type Function

;; List constructor is also useful, especially if you want to compute elements to be the result of some expression

(list 1 2 (+ 1 2))

=> (1 2 3)

;; Construct a list by adding a new element to the front

(cons 1 '(2 3 4))

=> (1 2 3 4)

Lists are primarily used to express Lisp forms / expressions. They are also efficient for operations that add/remove at the front of the list. For most other sequential data, you should consider using a Vector.

Maps

Maps are data structures that map arbitrary keys to values, similar to an immutable HashMap in Java.

;; A map of keywords to integers

{:red 1 :blue 2}

;; accessing a value with `get`

(get {:red 1 :blue 2} :red)

=> 1

;; associating a new value with a key (creates a new immutable map)

(assoc {:red 1 :blue 2} :green 3)

=> {:blue 2,:red 1,:green 3}

;; constructing a map from keys and values

(hash-map :foo 2 :bar 4)

=> {:foo 2,:bar 4}

With functions that expect a sequential data structure, maps operate as if they are a sequence of entries, where each entry is a [key value] vector

(def m {:blue 2,:red 1,:green 3})

(first m)

=> [:blue 2]

(count m)

=> 3

nil may be used as a map key or value, however this is usually not recommended since nil also signal the absence of a value and this can be ambiguous. e.g. all of the following evaluate to nil

(get {nil nil} nil) ;; nil key present, but value is nil

(get {} nil) ;; nil key not present

(get {:foo nil} :foo) ;; :foo key present, but value is nil

(get {:foo nil} :bar) ;; :bar key not present

Internally maps are implemented as radix trees based on the hash value of keys. This means that ordering is deterministic (since hashes are deterministic) but will appear random. Code using maps SHOULD NOT make any assumptions about map order.

Sets

Sets represent an unordered collection of distinct values, equivalent to a finite set on mathematics.

;; A set of integers

#{1 2 3 4}

;; The empty set

#{}

Sets can be tested for membership with the get function, which returns true or false based on whether the element is present:

(get #{1 2 3} 2)

=> true

(get #{1 2 3} 5)

=> false

Sets are particularly useful in cases where logic is required to compute intersections, unions and differences between sets. These operations have optimised support in the CVM, which makes such operations much cheaper than accessing or comparing elements individually.

(union #{1 2 3} #{3 4 5})

=> #{5,4,2,3,1}

(intersection #{1 2 3} #{3 4 5})

=> #{3}

(difference #{1 2 3} #{3 4 5})

=> #{2,1}

A key motivation for the inclusion of Sets in the CVM (besides their mathematical elegance) is to efficiently support systems that must keep track of a variable number of distinct values

- Trusted users authorised via an access control list

- Which users are still eligible to vote in an election, or have already voted

- Flags describing which optional terms apply to a smart contract

Internally sets are implemented as radix trees based on the hash value of elements. This means that ordering is deterministic (since hashes are deterministic) but will appear random. Code using sets SHOULD NOT make any assumptions about set order.

Indexes

Indexes are specialised ordered maps that support "Blob-Like" keys only (Blobs, Strings, Addresses, Keywords and Symbols). Entries are sorted based on the byte values of the keys, up to a maximum of 32 bytes.

;; Construct an index, note that the map is sorted in order

(index 0x1234 :foo 0x3456 :bar :5678 :baz)

=> {0x1234 :foo,0x3456 :bar,0x5678 :baz}

;; Keys with identical byte values in their content will overwrite previous entries (even if a different type!)

(assoc (index :foo 567) "foo" 789)

=> {"foo" 789}

Use an Index instead of a Map if both of the following are true: a) you need a sorted map b) you can strictly control the type of keys

Keywords

Keywords are symbolic names preceded by a colon (:) which are typically used to represent:

- short human-readable keys in data structures

- possible values for a set of flags, similar to an "enum" in many languages

- error codes such as

:TRUST - metadata keys such as

:callable

;; Keywords are literals that evaluate to themselves

:hello

=> :hello

;; Keywords can be converted to and from Strings

(name :hello)

=> "hello"

(keyword "hello")

=> :hello

Keywords of this form have been popularised in the Clojure language. The CVM implementation may perform some optimisations to make use of common keywords more efficient.

Technically, CVM Keywords can contain any UTF-8 characters, but for compatibility with the Reader, consistency with Clojure, for use in text files and by convention it is RECOMMENDED to limit character usage to the following:

- Alphabetic characters (lowercase or uppercase, case sensitive)

- Numerical digits

0to9(disallowed as the first character by the Reader, but OK in other positions e.g.:level7) - The symbols

*,+,!,_,?,<,>and= - The hyphen

-(preferred as a word separator)

A Keyword MUST have a length of between 1 and 128 UTF-8 bytes (inclusive). This size is motivated by the following considerations:

- Large enough for most sensible human readable names

- Small enough that Keywords are always embedded values in encodings

- Large enough to contain a 32-byte hex string with a prefix (note restriction on numerical digits at start of keywords)

- Discourage the use of Keywords for arbitrary content (use a Blob or String instead)

Symbols

Symbols are symbolic names used to refer to other values. They are similar to Keywords, however they are treated specially by the compiler as they are used to look up values in the current context / environment.

;; You can define a symbol to refer to any value you like, e.g. a Vector. This will consume some CVM memory.

(def bar [1 2 3])

;; Once a symbol is defined in the environment, it will evaluate to the value itself

bar

=> [1 2 3]

;; Trying to evaluate a symbol that is undefined will result in an :UNDECLARED error

foo

=> :UNDECLARED error

;; `count` refers to the core runtime function. This prints as `count` but is NOT the symbol: the result is the `count` core function

count

=> count

;; This is how code works! the symbol refers to a function, which is looked up then applied to the arguments

(count [0 1 2 3])

=> 4

It is sometimes useful to use a Symbol as a value in itself (without performing any lookup). In this case, it is possible to quote the Symbol, so that the symbol itself will be returned (rather than the value that it refers to). This can be done in two ways:

;; Quoting with the single quotation mark

'foo

=> foo

;; Quoting with the `quote` special form:

(quote foo)

=> foo

Records

Records are CVM data structures that behave like maps with a fixed set of keys. They are primarily used for internal data structures supporting the CVM. You cannot currently construct Records directly, but can access and read them:

;; Get the account status record for an account

(account #14)

=> {:sequence 1,:key 0x168e11d2512217576c30ec305ed672147125c9e20636fac29f4fca46cda0f003,:balance 132933333327304,:allowance 9999977,:holdings {},:controller nil,:environment {},:metadata {},:parent nil}

For practical purposes, Records behave as an immutable Map, and can be used in similar ways.

Functions

Functions are values in Convex Lisp that can be applied to zero or more arguments.

Key properties:

- They are full first class values, i.e. can be stored in data structure or passed as arguments to other functions

- They can optionally support variable arity (i.e. variable numbers of arguments)

- They operate as closures over lexically defined values

Applying functions

Function application is performed by evaluating a List where the function to be applied is the first element of the list, and the following elements are the arguments:

;; The `+` function adds together any number of numerical values

(+ 1 2 3 4)

=> 10

;; The `count` function counts the number of elements in a data structure:

(count [1 2 3 5 8])

=> 5

If the number of arguments is variable, you can use apply to apply a function to a sequence of arguments.

(def numbers [1 2 3 4 5])

(apply * numbers)

=> 60

Defining functions

Functions are typically defined with the defn macro, which creates a function and stores it in the current environment.

(defn square [x]

(* x x))

(square 12)

=> 144

Variable arities

Functions can support multiple arities by specifying different combinations of parameter lists:

;; A function with arity 1 and 2 specified

(defn greet

([a]

(str "Hello " a))

([a b]

(str "Hello " a " and b)))

(greet "Bob")

=> "Hello Bob"

(greet "Bill" "Ben")

=> "Hello Bill and Ben"

Functions can also support fully variadic arguments using the & symbol preceding a variadic argument

(defn average [& nums]

(/ (apply + nums) (count nums)))

(average 1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0)

=> 2.5

Variadic arguments may be included at any position in the parameter list, but to avoid ambiguity a maximum of one & may be used in any single binding list. Variadic arguments are not required to be placed in the final position, however it is recommended to do so by convention. An example where a non-termial variadic argument might be useful is where the arguments represent a "stack" and it is helpful to bind the last argument representing the top element of the stack for special treatment.

Higher order functions

Higher order functions are functions that themselves take functions as arguments. This is fully supported on the CVM, and often results in cleaner, more robust code than would be achieved with equivalent imperative programming style.

A good example is map, which applies a function to all elements of a collection, avoiding the need for an explicit loop:

;; The inc function simply increments an Integer value

(inc 7)

=> 8

;; map can be used with inc to increment all elements of a collection

(map inc [1 2 3 4])

=> [2 3 4 5]

Another very useful higher order function is reduce, which can be used to sequentially apply a function to create an accumulated result:

(defn square [x] (* x x))

(defn sum-of-squares [coll]

(reduce (fn [acc x] (+ acc (square x))) ; Function to add squares to an accumulator

0.0 ; initial accumulator value

coll)) ; the collection argument to reduce over

(sum-of-squares [1 2 3 4 5])

=> 55.0

Anonymous functions

It can sometimes be convenient to create a function without storing it against a symbol in the environment. This can be done with the (fn [...] ...) anonymous function constructor.

(map

(fn [x] (* x x x)) ; Anonymous function to cube a number

[0 1 2 3 4])

=> [0 1 8 27 64]

Returning values

A return expression can be used to return early from a function with a given result:

(defn foo [x]

(return (str x)) ; Early return with a result

(fail "Shouldn't happen")) ; This line never gets executed

(foo 678)

=> "678"

In the absence of a explicit return, the result of a function will be the result of the final expression executed.

Floating point

Convex Lisp supports IEE754 double precision floating point mathematics with the built-in Double type. This is important for many domains where Integer values may be inconvenient or introduce inaccuracies, e.g. in statistical or pricing applications. Double support is also important so that Convex Lisp can express a superset of JSON.

;; Double values are literals, just like Integers

12.45

=> 12.45

;; Mathematical operations are supported for Doubles

(+ 1.2 3.4)

=> 4.6

;; Some mathematical operations always produce double results

(sqrt 16)

=> 4.0

;; You can convert any other number to a Double (including big integers)

(double 100000000000000000000000000000000000)

=> 1.0E35

;; Truncation to IEE754 Double precision is automatic when required (this is done by the Reader)

12.6678347835634781562349785632948756

=> 12.667834783563478

In general, operations that mix Integer and Double values will return a Double value.

(+ 1 2.0)

=> 3.0

(+ 1 2)

=> 3

There are special Double literals for NaN and +/- Infinity. Applications using Double values should be aware of expressions that might produce such results and handle them accordingly.

(sqrt -1)

=> ##NaN

(/ 1 0)

=> ##Inf

(- 4 ##Inf)

=> ##-Inf

Equality and comparisons

Value equality

The = function tests for equality between any values, returning a Boolean that is true if and only if all values are equal:

(= 123 123)

=> true

(= :foo "foo")

=> false

Value equality in Convex Lisp is strict and corresponds exactly with identity of CVM values (i.e. they must have the same encoding and Value Id)

Numerical equality

The == function tests for numerical equality. This is less strict than =. In particular it should be noted that Integers and Doubles can be numerically equal while not being identical CVM values (i.e. equality according to =)

(= 1 1.0)

=> false

(== 1 1.0)

=> true

Numerical comparison

The <, >, <= and >= symbols perform numerical comparison in the conventional fashion. Note that they support variable arities and mixtures of numerical types:

(< 1 3)

=> true

(>= 2.0 2)

=> true

(> 10 2 4.3)

=> false

The nil value

The value nil is an important special value. While usage may depend on context, it is typically used to mean "no value" or "not found".

Frequently, it is used to indicate when something is not found in a data structure, e.g.

;; Trying to `get` a value from a map for a key that does not exist.

(get {:foo 1, :bar 2} :baz)

=> nil

When passed to functions that expect a data structure, nil is interpreted as an empty data structure:

;; Concatenating vectors with `nil`

(concat [1 2] nil [3 4])

=> [1 2 3 4]

;; Intersecting sets with `nil`

(intersection nil #{1 2 3})

=> #{}

;; Merging maps with `nil` leaves them unchanged

(merge {:foo 1} nil)

=> {:foo 1}

;; `nil` is considered to be `empty?`

(empty? nil)

=> true

NOTE: while nil may behave like an empty data structure in many contexts, it is a distinct value from the empty data structures ([] () {} and #{}). None of these values are considered equal to each other. In particular, functions that are expected to return a data structure should normally produce an empty data structure rather than nil if they succeed.

When used in conditional expressions, nil is considered as false (see section on conditional expressions for more details)

When used in JSON-like data structures, nil maps to the JSON value null.

Conditional Expressions

if macro

The most common form of conditional expression is the if macro, which evaluates the first (test) expression to determine whether the second (true) or third (false) expression should be evaluated to determine the final result.

(if true

"This will be the result"

"This will never happen")

The false branch may be omitted, in which case the result will be nil

cond special form

If multiple test expressions are required, the cond special form allows this, returning the result for the first conditional expression matched (or an optional default expression if none match).

(def a 13)

(cond

(< a 10) "a is too small")

(> a 20) "a is too big")

"a is just right")

NOTE: The if macro expands to a cond expression in the standard Convex Lisp implementation. Using cond may be mildly more efficient in performance sensitive code, as it avoids one additional step of macro expansion.

Truth Values

In conditional expressions, results are determined by whether the evaluation of a test expression is "truthy" (like true) or "falsey" (like false).

The rule is simple:

falseor the valuenilare considered "falsey"trueor any other value are considered "truthy"

NOTE: A key reason for this rule is for convenience and simplifying code: (if (not (nil? (lookup-thing a b))) ...) can often become (if (lookup-thing a b) ...). This is consistent with behaviour in other Lisps, where it is frequently referred to as "nil-punning".

Importing and referencing other accounts

It is frequently useful to refer to symbols in the environment of a different account from the one currently being used. Examples where this is important:

- Referring to functions in shared library code

- Examining a data structure in an Actor account

- Defining a value once and referring to it from many user accounts

Namespace Lookup

Referring to a value in another account is made convenient with the / lookup syntax:

;; A symbol in the current account (i.e. *address*)

foo

;; A symbol in a different account

#42/foo

;; Any expression can be used to define the target account

(def other #42)

other/foo

Referring to functions and data structures in this way is usually more memory efficient, and recommended in most cases where there is no need for multiple accounts to keep a duplicate copy of the same value.

A very common use case is importing a library of code or values. Fot this purpose, the import macro is provided that creates an alias to any account via the Convex Name System (CNS)

;; Import a library

(import convex.fungible :as fun)

;; Use the library alias for references

(deploy (fun/build-token {:supply 1000000}))

Nested lookups

It is possible to nest lookups, since the target account is defined by an expression, and a lookup is a valid expression in itself.

;; This works providing that `other-alias` is defined in the account specified by `alias`

alias/other-alias/target-symbol

;; This is equivalent to using a temporary intermediate alias:

(let [intermediate-alias alias/other-alias]

intermediate-alias/target-symbol)

While possible, nested lookups would be unusual. A possible use case would be adding a layer of indirection so that the intermediate account can switch to different versions of a final destination account, for purposes of version control or providing alternative implementations of a component.

Security implications - IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT NOTE: while namespaced lookups refer to a value in another account, they do not change the security context, therefore code from another account that is executed will still run within the current account (*address*). To avoid security risks users MUST ensure they do not execute untrusted code. It practice this means:

- Always review whether you trust an account that you

import - NEVER execute a function from an untrusted account directly

- Wrap execution of potentially untrusted code in a

queryto eliminate the possibility of any adverse side effects

(import some.untrusted.account :as danger)

;; This is safe because you are just reading a value, but you can't trust the value of `do-something`

danger/do-something

;; DON'T DO THIS - it will execute any code in the `do-something` function in your current account

(danger/do-something)

;; This is safe from side effects, though still potentially unwise: an attacker could burn your juice, or cause an error

(query (danger/do-something))

Be aware that CNS references MAY change, i.e. (import some.library.account as lib) may result in a reference to a different underlying account in future executions. Ideally, the import should only be executed once, and the value of the alias lib should be examined afterwards to ensure it refers to the correct account (e.g. #43567). If a malicious change to CNS is considered a risk, it may be preferable to define the alias to a known trusted account directly e.g. (def lib #43567)

Calling actors

Within a set of accounts that a user controls, the CVM provides a complete general purpose programming language where any code can be executed and data can be modified.

However, for meaningful decentralised systems to operate, it is necessary to interact with other accounts that the user does not control, and which may provide important functionality such as trusted smart contracts or shared digital asset implementations. This can be done with a call that transfers execution control to another account.

Call Syntax

A call should be regarded as an instruction to an actor to perform an action on the caller's behalf.

The call takes the following arguments:

- A destination Address, which can be any valid account address (or a scoped address of the form

[#1579 :some-value], see below) - An optional offer of Convex Coins, which the destination account may choose to accept from the caller

- A function invocation (which may include any arguments)

Typical usage:

(call #67 (some-function :arg1 :arg2))

Usage with an offer of 1,000,000 copper:

(call #67 1000000 (some-function :arg1 :arg2))

Executing a call expression will:

- Check if the target account exists

- Check if the function name exists in the target account and has the

:callablemetadata set to true - Check if the current account has enough Convex Coins to reserve for the offer (if set)

- If and only if all checks pass, switch the execution context to the target account and run the specified function with the given arguments

- Once complete, control will return back to the caller with a result value for the call (or an error if one is thrown)

Callable functions

A callable function is any function with the :callable metadata set to true. This instructs the CVM to allow the function to be a target of a call. An example definition of a callable function that might be defined in an actor account is as follows:

(def visitor-count 0)

(defn ^:callable visit [name]

(set! visitor-count (inc visitor-count))

(str "Hello " name " you are visitor number " visitor-count))

This can be called from any other account as follows:

(def actor #456756) ;; refer to whatever the actor account is

(call actor (visit "Bob"))

=> "Hello Bob you are visitor number 1"

(call actor (visit "Mary"))

=> "Hello Mary you are visitor number 2"

Important points to note:

- The callable function modifies a value

visitor-countthat is defined within the actor. Only the actor itself can adjust this value. This demonstrates how actors can have control over their own internal state, but still allow callers to interact in a way that modifies this state in a predictably defined manner. - Other users can observe

visitor-count(but not modify it!) e.g. using a lookupactor/visitor-count. This demonstrates how actor state is publicly visible. However, users should exercise caution when referring to internal actor implementation details: it may be preferable to use a separate callable function to query state, especially if it is possible that implementation details may change. - Assuming that the actor is immutable (i.e. has no external access or upgrade functionality) then the visitor count will be correctly managed for all time. This demonstrates the use of an actor as an unstoppable decentralised program that serves a clear purpose.

Scoped calls

It is frequently useful for an actor to manage multiple instances of entities of a particular type (e.g. a large number of concurrently running auctions in an auction house). In such cases, we can refer to each entity with a scoped address which is a vector that includes both the actor address and an identifier for the specific entity e.g. [#123 101].

To support this usage, call may optionally support the provision of a scope specified as follows.

(call [#67 :scope-value] (some-function :arg1 :arg2))

A scoped call operates in the same way as any other call, except that the special value *scope* will be set to the value passed in the scope vector (in this case :scope-value). *scope* will be nil if no such scope value is used.

Values or identifies used as a *scope* are defined by the actor: any CVM values may be used. It is however STRONGLY RECOMMENDED to enforce unique IDs e.g. allocating IDs using an incrementing integer counter for each entity created.

Usage of scoped calls is ultimately an interface design decision for creators of actors. It is possible to achieve the same functionality with an additional ID argument to the call, for example. Experience suggests however that using scoped addresses simplifies writing generic user code that must refer to multiple entities provided by multiple actors, so it is RECOMMENDED to do so if your actor manages multiple entities.

In most cases, entities managed by an actor will have a limited lifecycle. It is STRONGLY RECOMMENDED that:

- Live entities are stored in a data structure indexed by

*scope*for efficient access and existence checks (this should normally be a hash-map or index) - Actors provide a facility to delete expired entities (this allows memory reclaim to the benefit of whoever does the cleanup)

- Scoped calls that reference a deleted/non-existent entity should fail

- There is no way for a new entity to be created with the same ID as a deleted entity (using an incrementing counter solves this)

Security context

The current account is *address*. Any code executing has full control over this account, including the ability to modify the account's environment with def or set!.

The account for which the transaction was initiated is *origin*. This remains unchanged for the entire transaction, and is initially equal to *address*

The account that transfered control to this account, if any, is *caller*. This is nil initially, but will be the address of the account that executed any call to this account.

IMPORTANT: From a security perspective, *caller* should be regarded as the account to check for authorisation to perform any action within an actor, since that is the account that made the call and requested for the action to be performed. DO NOT rely on *origin* for security checks.

Call security

For callers

Within the scope of the call the target actor executes within it's own account context. This protects the caller : the actor does not have the ability to modify the caller's account and cannot impersonate the caller for the purpose of interactions with other actors (it must act on its own behalf).

As with all CVM code execution, juice costs are paid by the account that initially executed the transaction (*origin*). It is possible for an actor to burn all available juice (in which case the transaction will fail). While the downside is limited by available juice, users should be aware that malicious or badly written actors may consume more juice that desired, and avoid calling untrusted actors.

For actor developers

IMPORTANT SECURITY NOTES:

- Actor creators should remember that any account may call a callable function: they are a public API

- Actor code SHOULD always perform authorisation checks against

*caller*to see if the caller has the right to perform the requested action, and fail with a:TRUSTerror otherwise. The only exceptions to this are operations that are truly intended for anyone to be able to perform (e.g. depositing in a public donation box) - The

:callablemetadata should only be set for functions that are intended to be part of a public actor interface. Each such function represents any entry point that increases the size of public actor API that must be security audited.

Other syntax

Whitespace

The Convex Lisp reader does not distinguish between different types of whitespace. Any number of tabs, commas, spaces and new lines are all considered equivalent. Programmers may find this useful for formatting source code for better readability.

(+ 3,4)

=> 7

( + 3 4 )

=> 7

(+

3

4)

=> 7

In some cases, whitespace MAY be omitted, where the syntax is unambiguous to the reader. This is NOT RECOMMENDED, since it may harm legibility and does not result in any on-chain data savings.

(+(+ 1 2)(+ 3 4))

Comments

Line comments include any text after a semicolon ; up to the end of the line. Comments are considered whitespace by the reader:

; This is a comment

;;;;; So is this

The reader macro #_ can be used to instruct the reader to ignore any single form. This can be useful for temporarily ignoring chunks of code:

(+ 1 #_(this is a

block of code

which will not compile

and is ignored)

2 3)

=> 6

Metadata

Convex Lisp supports metadata on any value. When metadata is applied to a value, it creates a Syntax object, which wraps both the metadata and the annotated value.

The ^ symbol may be used to add metadata to a value and create a Syntax object, or you can use the syntax function to construct one:

;; A syntax object adding a metadata map to a vector (Note the quote: compilation would otherwise strip the metadata)

(quote ^{:foo "This is a metadata value"} [1 2 3])

=> ^{:foo "This is a metadata value"} [1 2 3]

;; The `syntax` core function can be used to construct the same syntax object as above

(syntax [1 2 3] {:foo "This is a metadata value"})

=> ^{:foo "This is a metadata value"} [1 2 3]

;; Metadata can be empty

(syntax [1 2 3])

=> ^{} [1 2 3]

;; A keyword can be used as a shortcut to set a single metadata flag to true

(= ^:mark [1] ^{:mark true} [1])

=> true

Syntax objects can be wrapped and unwrapped with syntax, meta and unsyntax:

;; Unwrap the value from a syntax object

(unsyntax (syntax [1 2 3] {:some :metadata})

=> [1 2 3]

;; Unwrap the metadata from a syntax object

(meta (syntax [1 2 3] {:some :metadata}))

=> {:some :metadata}

Metadata can be attached to any definition in the environment:

;; Define a symbol with metadata

(def myval ^{:level 12} [1 2 3])

;; Lookup metadata for a symbol

(lookup-meta 'myval)

=> {:level 12}

Key use cases for metadata:

- Control behaviour of definitions in the environment e.g.:

- The

:callablemetadata tag indicates a callable actor function - The

:staticmetadata tag indicates a definition that should be inlined by the compiler - Provide on-chain documentation for key functions, conventionally stored under the

:docfield of metadata - Allow custom expansion / compilation logic for DSLs, e.g. type annotations

;; example of accessing documentation metadata via the `doc` macro

(doc count)

=> {:description "Returns the number of elements in the given collection, blob, or string.",:signature [{:return Long,:params [coll]}],:errors {:CAST "If the argument is not a countable object."},:examples [{:code "(count [1 2 3])"}]}

The Reader

The Convex Lisp Reader is a software component that converts UTF-8 strings into CVM data structures.

E.g. the String "(+ 1 2 3)" is converted by the Reader into the list (+ 1 2 3)containing 4 elements where the first element is the Symbol + and the following elements are Integers.

The Reader is not available on chain - it is intended for use in client code or tools that communicate with the Convex network, such as a REPL terminal.

The reader syntax in the convex-core reference implementation is available as a ANTLR Grammar

NOTE: Use of the Reader is not mandatory: it is possible to construct Convex Lisp forms programmatically (or even directly build pre-compiled CVM Ops) rather than parsing a String via the Reader. This may offer marginal performance benefits in some applications, e.g. JVM based systems that need to construct a large number of transactions.

Coding Conventions

The following conventions are recommended and/or generally utilised in Convex Lisp libraries:

Hyphenation

Hyphens are generally preferred to separate symbol names, e.g. do-something (rather than do_something or doSomething). This makes no difference to the CVM, but is primarily done for consistency with other Lisp based languages.

Constant naming

Prefer capitalised names like PRICE for global configuration variables and constants. This is to differentiate clearly from local, temporary or dynamically changing values.

Keywords vs. Symbols

If in doubt whether to use Symbols or Keywords, the following may be helpful:

- Symbols are best when referring to values defined in the current environment (e.g. using

def) - Keywords are best as keys in data structures or literal / constant values since they do not require quoting for such usage

Comma usage

Commas are considered whitespace, so there is no functional difference between [a b c] and [a,b,c].

We recommend using spaces instead of commas, unless the comma helps with source code readability or compatibility. Examples where commas may be helpful:

;; Commas may be helpful to visually group keys and values in maps

{:a 1, :b 2, :c 3}

;; Commas may be used to make vectors compatible with JSON format. This is a valid JSON array:

[1, 2, 3]

Clojure Consistency

Where possible, coding style should be consistent with Clojure which shares a very similar syntax to Convex Lisp.

The Clojure Style Guide may be informative.

Performance tips and tricks

Efficiency is an important concern for decentralised systems, as all computation and storage comes with a cost. Users of your product will thank you for minimising their transaction fees.

Here are some methods for developing more efficient code in Convex Lisp.

Do complex processing elsewhere

In many cases, there is no point doing computation on the CVM at all: consider carefully if the processing can be done on the client or a product backend server instead.

Some common examples:

String parsing

Do not attempt to parse strings in Convex Lisp (or on the CVM generally). This is almost always a bad idea: it is computationally expensive and likely to be error prone. Formats are also likely to change which may cause maintenance headaches for on-chain code.

Instead: parse strings on the client or server with well tested libraries (e.g. ANTLR) and send to the CVM as CVM data structures. This is the approach taken by the Convex Lisp Reader, for example.

Human readable output

Do not try to produce human readable output for users on the CVM. Code to generate such output almost certainly belongs on the client or backend server. Apart from the execution cost, there are additional practical problems with this approach:

- Text is likely to change. You don't want to be updating CVM code or data every time marketing changes some copy or formatting rules.

- You definitely don't want to be dealing with things like internationalisation on the CVM.

Instead: return a well defined integer value, keyword or other data structure that represents the relevant information and can be converted to the right human readable message on the client and/or server.

Don't store content

The CVM is not the place for storing static content such as images, text or other large binary files.

Instead: use the Data Lattice, IPFS or a traditional web server / CDN that clients can download content from.

If you absolutely must validate content against an on-chain record, store a single 32-byte hash of the content. This can be the merkle root of a large tree of content if necessary. Clients can hash the content and check this for authenticity / integrity.

Beware loops

Loops will often be at least O(n) in the size of the data structure they are iterating over. This can include explicit loop constructs or a map or reduce which implicitly loop over elements of a data structure.

Usually, looping in CVM code indicates a design problem that will get worse as data size grows.

Instead: Design your data structures and actor APIs so that data can be accessed or updated directly without looping. Typically, this might involve accessing records directly via a key in a Map. If necessary, clients can do loops themselves and access the content via multiple queries / transactions.

Minimise encoding lengths

It will be more efficient (and save memory costs) if you use data values with shorter encodings. If you expect to store large numbers of similar data structures, it is definitely worth minimising the size of each instance.

You can use the encoding function to see the byte representation of any value. As an example you can see that the encoding of true is actually more memory efficient than the integer 1

(encoding 1)

0x1101

(encoding true)

=> 0xb1

Other tips for shortening encodings:

- Use a vector

[1 2]instead of a map with fixed keys{:field1 1 , :field2 2} - Use shorter Keywords e.g.

:finstead of:failure - Avoid having entries in maps where the value is a default value like

nilor0e.g.{:name "Bob" :ferraris 1 :bugattis 0 :lambos 0}becomes{:name "Bob" :ferraris 1}. You code can provide a default value ingetwhen reading the key e.g.(get person-record :lambos 0) - If the same code is going to be duplicated in multiple accounts, put it in one account (or a library) and refer to that from the other accounts

- Use a Set rather than a Map with dummy values if the values don't matter

nil0trueandfalseonly require 1 byte of encoding. These are the smallest CVM values.

Pre-compilation

If you compile Convex Lisp code before sending code to the CVM, you avoid the cost of compilation. This may be significant for complex expressions, especially if they involve macros. While unimportant for small one-off transactions, this may be valuable if you are sending a lot of transactions to Convex.

There is no strong reason to avoid pre-compilation unless the compilation depends on something that might change in the global state and you need compilation to happen atomically in the same transaction as it is executed.

Notable Differences vs. other languages on decentralised VMs

Many decentralised systems offer virtual machines that are Turing complete and can execute code using one or more general purpose programming languages. Ability to do this however does not mean that it is easy to build efficient, secure and capable decentralised economic systems.

We believe the following features of Convex Lisp, among others, offer substantive improvements over typical existing solutions:

- Functional Programming: full support for the lambda calculus and first class functions

- Code is data: Convex Lisp is a fully homoiconic language, with code expressed in its own data structures

- On chain compiler: Convex Lisp on-chain code can perform code generation, compile and deploy new Convex Lisp code

- Big Integer support: arbitrary precisions integers are supported as standard, avoiding risks of overflow (e.g. 256-bit fixed words)

- Floating point support: Full IEEE754 Double compatibility, which are more suitable than integer mathematics for many purposes

- Orthogonal Persistence: storage is automatic, with no need to explicitly store data. Extremely large data structures are supported (including larger than machine memory) and are loaded when accessed on demand.

- Extra Types: A full range of general purpose value types including: Sets, literal Keywords, sorted Indexes, UTF-8 Strings, Blobs etc.

- Memory accounting: Economic system for memory management. See CAD006

- Powerful macro capability: ability to fully customise the language with expanders. See also CAD009

We hope that developers will find the tools provided in Convex Lisp a compelling solution as we continue to build open economic systems.

Future plans

Convex Lisp will continue to develop alongside Convex. Key goals beyond Convex V1 include:

- Backwards compatibility: we must never break the behaviour of existing correct code. New changes will be strictly additive.

- Type System: The CVM already has a rich type system. We will explore options to make this more visible and useful to developers: in particular support for gradual typing may be appealing

- Cryptographic primitives: support for cryptographic operations natively in Convex Lisp. We note that most cryptographic operations should be performed at the level of client or peer implementations rather than on the CVM, but support for some such operations on the CVM may be justified where they enable important use cases (e.g. homomorphic encryption)

- 32-bit floats may be important as a key additional data type, particularly given their prevalence in AI systems. We will support these if and when they are natively supported on the CVM.